Class Report: Three Years of Intercultural Communication

2025/1/28

Michal MAZUR (Asst. Prof.)

When I first stepped into my classroom to teach Intercultural Communication for Living in a Global Society at Hokkaido University three years ago, I didn’t know exactly what to expect. I felt a mix of anticipation and curiosity, driven by a desire to tackle an issue I had observed throughout my teaching career. This wasn’t just about language—it was about understanding cultural nuances, interpreting unspoken signals, and building genuine connections.

That realization inspired me to design a course that would go beyond traditional language teaching. I wanted students to explore how culture shapes communication and learn practical skills for connecting with people from diverse backgrounds. The course became a space where students could not only develop empathy and cultural awareness but also prepare for real-world interactions in an increasingly interconnected world.

Three years later, I am more convinced than ever that this work is crucial. Intercultural competence has become a necessity, not just a skill. Learning to navigate cultural differences, communicate with understanding, and collaborate across cultures equips students for success far beyond the classroom.

Why Intercultural Communication Matters

This course was born out of a repeated observation I’d made during my teaching career: students in Japan often excelled in language mechanics but struggled in real-world interactions. They could construct grammatically perfect sentences but lacked the ability to interpret cultural nuances.

For instance, when is silence appropriate in a conversation? In Japan, a pause can signal respect or thoughtfulness, but in many Western cultures, silence might be interpreted as awkwardness or disinterest. This example illustrates Edward T. Hall's theory of high-context and low-context communication. High-context cultures like Japan rely heavily on non-verbal cues, while low-context cultures prioritize direct, explicit communication.

If not addressed, these cultural differences can lead to misunderstandings. Imagine a Japanese student in a low-context environment who interprets prolonged silence as respectful, only to discover it’s perceived negatively. These subtleties go beyond language; they define how people connect and collaborate.

The stakes are high. In professional settings, a lack of intercultural understanding can lead to miscommunication, strained relationships, and missed opportunities. Preparing students to recognize and navigate these differences is crucial not only for their personal growth but also for their future careers.

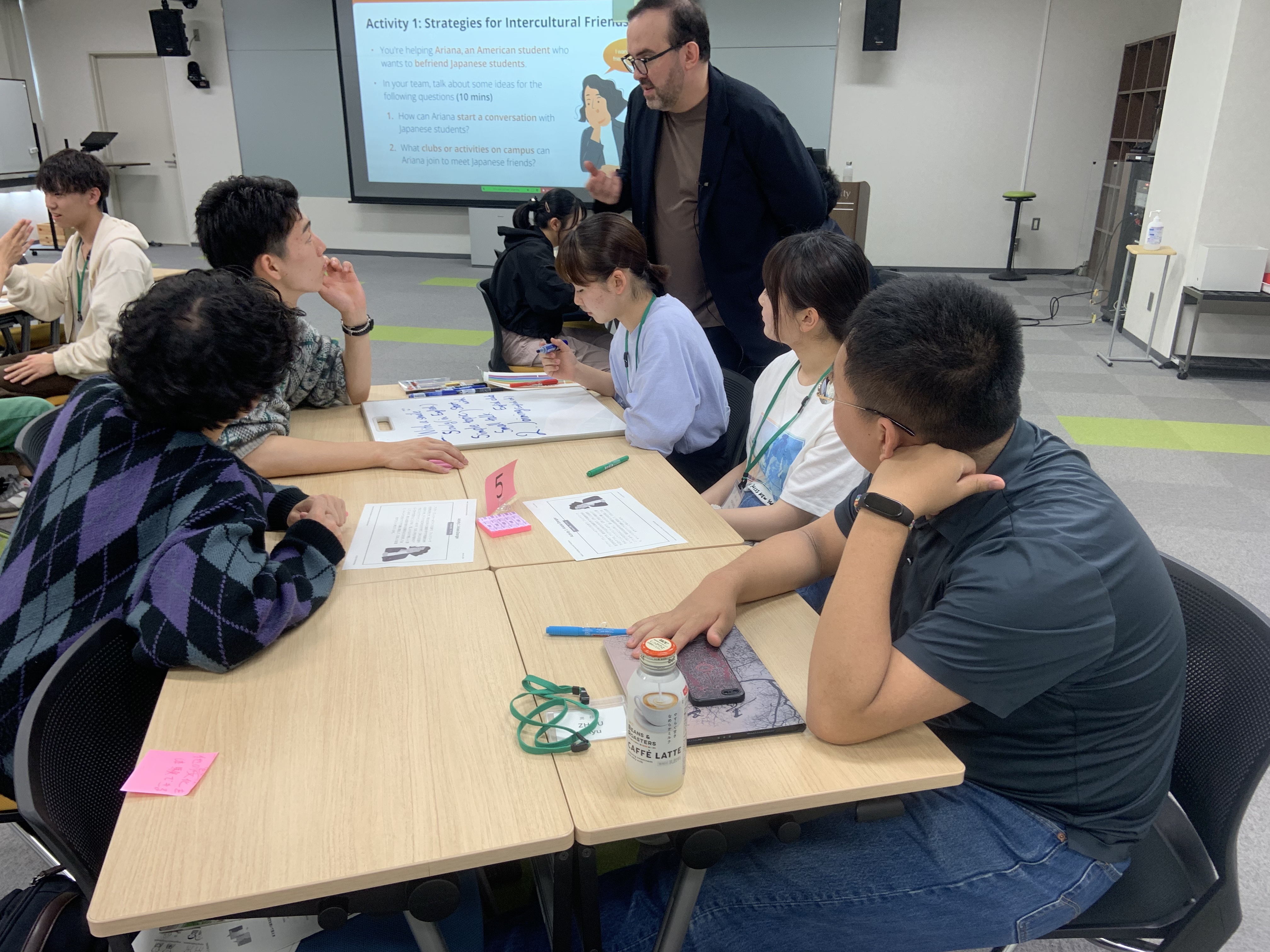

Picture: In-class teamwork

Designed to Build Real Skills

From the beginning, I knew this course needed to be experiential rather than theoretical. I designed it to encourage active participation, self-reflection, and collaboration. Students weren’t just passive recipients of knowledge but active contributors, bringing their unique perspectives and experiences to the table.

One of the course’s central features was its use of real-life case studies to simulate intercultural scenarios. Students analyzed situations where cultural misunderstandings, such as misinterpreted gestures or differing communication styles, had occurred. For example, one case study involved a Japanese manager working with an American team. The manager’s indirect feedback was misunderstood as unclear expectations, leading to delays in the project. Students discussed how clearer communication or cultural awareness could have resolved the issue.

We also used role-playing exercises, in which students acted out scenarios involving cultural conflict or misunderstanding. In one exercise, a student played the role of a guest in a low-context culture who accidentally offended their host by misinterpreting direct feedback. By switching roles, students gained a deeper understanding of both perspectives.

We invited international students and teaching assistants to share their experiences to bring additional perspectives into the classroom. These guests represented diverse cultural backgrounds and offered invaluable insights. One international student from Egypt shared their experience navigating Japanese cultural norms, from the emphasis on indirect communication to the subtleties of group dynamics. Their story sparked rich discussions about approaching unfamiliar cultural settings with an open mind.

Picture: Guest commentators

Using Real Stories to Build Empathy

One of the most impactful aspects of the course was the inclusion of video testimonies from international students who had experienced culture shock in Japan. These videos became windows into their real emotions and struggles.

For example, one video featured a student from China who spoke about their challenges adapting to Japan’s high-context communication style. They recounted feeling lost when indirect hints went unnoticed, only to realize later that they had unintentionally caused discomfort. This testimony resonated deeply with Japanese students, many of whom had never considered how others might perceive their communication style.

After watching these videos, students engaged in group discussions to unpack the stories, reflect on their own experiences, and consider how they might approach similar situations. Such activities helped foster empathy and understanding, often more important than just theoretical concepts.

What Students Learned and How It Changed Them

The results of the course were both measurable and deeply personal. Self-assessments revealed significant growth in students’ confidence and intercultural competence. Beyond the numbers, their reflections offered a glimpse into the transformative impact of the class.

One student shared: “I learned that cultural differences aren’t just obstacles—they’re opportunities to grow and learn. This class gave me tools to navigate those differences with confidence.”

Another commented: “Before this course, I was afraid of making mistakes when communicating with people from other cultures. Now, I see mistakes as a chance to ask questions and improve.”

Such reflections highlight a shift in mindset. Students began to see intercultural communication not as a challenge to overcome but as a skill to embrace.

Picture: Dr Michal Mazur giving a lecture

Challenges and Future Directions

No course is without its challenges. One recurring piece of feedback from students was the desire for more informal conversation time. While structured activities and case studies were valuable, unstructured discussions could help build relationships and deepen understanding.

Another challenge was ensuring diversity within the class. At Hokkaido University, the lottery-based selection process for freshman seminars limits the number of international participants. To address this, I’ve worked to bring in international teaching assistants and guest speakers to enrich the classroom experience.

Looking ahead, I would consider more opportunities for casual intercultural interactions, such as informal discussion sessions or collaborative projects that extend beyond the classroom.

Lessons for Educators

If there’s one thing I’ve learned over the past three years, it’s that intercultural communication is much more than avoiding misunderstandings. It’s about creating connections, fostering empathy, and building bridges across cultural divides.

My advice to educators considering similar courses is simple: prioritize experiential learning. Give students the tools to reflect on their own cultural assumptions and engage meaningfully with others. Create a supportive environment where mistakes are seen as opportunities to grow.

Ultimately, the goal is not just to teach students about other cultures but to help them see the world through someone else’s eyes.

References

- Deardorff, D. K. (2006). The Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241-266. DOI: 10.1177/1028315306287002

- Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond Culture. Anchor Books.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Prentice Hall.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (1997). Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education. Harvard University Press.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. Sage Publications.

▶Center's Note